Follow My Journey

Birding Colombia’s Perijá Mountains

The Perijá Mountains have aways been somewhat mythical to me. A small mountain range along the Venezuela-Colombia border that for decades was almost completely inaccessible to birders. Due to its relative isolation from the rest of the Andes, the Perijá mountain range is home to at least 5 endemic species of birds, with more potential splits in the future.

As we arrived in Manaure, a town about 1.5 hours from the Perijá ProAves Reserve, we revieved some troubling news. We had arranged ahead of time to be driven the rest of the way to the reserve in what we were told was a "special vehicle" that could handle the rough road up the mountain. This "special vehicle" ended up being a pair of rickety tuktuks, and our contact Oscar had just informed us that due to some extreme rain higher up the road, he wasn't sure if we'd be able to make the journey. Having no other option, we had to hope for the best as we loaded our bags and ourselves into the tuktuks and began the long ride up the mountain. The first few miles of the road were perfectly fine, even paved in some parts, but after about half an hour, the conditions rapidly deteriorated. As we hit the rougher sections of the road, it continued to rain harder and harder until it was almost impossible to see out of the front of the tuktuk. Despite my confidence in our driver, I was starting to feel a little worried. After another hour of being jostled about by the bumpy road, soaked by the torrential rain, and holding on for dear life, we finally made it to the reserve.

Immediately, I was greeted by several lifers. Longuemare's Sunangels swarmed the hummingbird feeders, with Black and Bluish Flowerpiercers trying to get a taste as well. I watched the feeders for only a few minutes before a Chestnut-crowned Antpitta appeared. With their long-legs, short tail, and overall round appearance, antpittas are one of my favorite bird families in South America, and it was an amazing experience to finally see one. As the sun slowly set over the Perijás, I prepared myself for an exhausting 3 days of hiking, birding, and naturalizing one of the most unique regions of Colombia.

Chestnut-crowned Antpitta (Grallaria ruficapilla)

Early wake-ups are an unfortunate reality of being a birder, and that day was no different. I reluctantly got out of bed at 4:45 in the morning to be ready for a long ascent to the higher elevations of the mountain range. The first 45 minutes of our walk were in almost total darkness, accompanied by nothing but the calls of Yellow-throated Toucans and Highland Tinamous echoing through the valleys of the Perijás. As the sun began to rise, we began to spot Blue-capped Tanagers, Tyrian Metaltails, and Rufous-collared Sparrows along the road, with Band-tailed Pigeons zooming by overhead. With top speeds nearing 60mph these pigeons are one of the fastest flying birds in the world, sometimes drawing comparisons to jet bombers due to the loud sounds produced while flying at top speed.

It wasn’t until we reached the páramo that we started to see some of the specialties of the Perijá region. Over the first hour and a half of our walk, we had been seeing many Tyrian Metaltails, a small, short-billed hummingbird that is quite common in mountainous regions from Venezuela all the way to Bolivia. Despite being such a common bird, we painstakingly examined each and every individual we saw, hoping to turn it into the rarer Perijá Metaltail. Overall, these birds look quite similar, with the main difference being the tail color. The more common Tyrian Metaltail has a bluish tail, while the Perijá Metailtail’s is more coppery colored. Needless to say, it can be quite annoying to differentiate these birds in the field. We finally got our eyes on a good candidate just after reaching the first stretch of páramo. Despite this bird being very uncooperative, never staying still for more than 2 seconds at a time, we were confident enough to call it a Perijá. With the first of the five endemic birds checked off the list, we were off to a hot start.

Tyrian Metaltail (top), Perija Metaltail (bottom)

These endemics weren’t the only targets however. With this being my first time really birding the Andes, pretty much every high elevation species was a lifer for me. Within my first few minutes in the páramo, I easily got my eyes on several Rufous-breasted Chat-Tyrants, a White-throated Tyrannulet, Rufous Spinetails, a Crimson-mantled Woodpecker, and much more. One of my favorite non-endemic lifers of the Perijá trip was the Red-crested Cotinga. Despite being one of the less showy cotingas in Colombia, Red-crested is one of my favorites. The subtle contrasts between the many shades of gray and black, along with the deep red crest and red eye make it such an interesting bird to observe.

Red-crested Cotinga (Ampelion rubrocristatus)

As we continued higher and higher into the mountains, we had two main targets. The Perijá Thistletail, and the excruciatingly difficult Perijá Starfrontlet. The starfrontlet is a gorgeous, long-billed hummingbird that can elude even the most experienced birders that visit the region. This difficult bird has only been observed around 100 times on ebird, and only once on iNaturalist. Compare that to a bird like the Mallard, with 18.3 million ebird observations and 617 thousand on iNat, and you can see how this bird might be tough to see. Despite waiting for over 45 minutes at what seemed like the perfect spot for this species, we came up empty handed and were forced to move on if we wanted to get the rest of our targets.

Unfortunately for us, one of our biggest targets, the Perijá Thistletail was only found along the highest portions of the road, and we had a lot more walking left to do. The birding along the road was much of the same. Rufous-breasted Chat-Tyrants and Rufous-collared Sparrows were by far the most common species we encountered along the road, with surprising numbers of Red-crested Cotingas regularly spotted perched on the very tops of the few trees that could survive this elevation. Despite the overall low bird diversity, we did encounter a few more lifers. We spotted several Streak-throated Bush-Tyrants, living up to their name by seemingly always being perched on the tops of large bushes. The repetitive song of the Andean Pygmy Owl was a welcome surprise around 10am, along with the distant calls of a Golden-headed Quetzal echoing through the mountains.

Rufous-breasted Chat-Tyrant (Ochthoeca rufipectoralis)

Finally, around midday, we encountered one of our last bird targets of the day. As we were scanning the cliffs for what would be my lifer Andean Condor, we noticed a small bird darting around in a bush less than 100 feet down the hillside, A Perijá Thistletail! Despite being an incredibly boring bird, almost entirely made up of dull grays and browns, I was elated to finally be able to observe this amazing endemic species. As we decided what to do next, I opened up google maps to see how close we were to spots for any of our other targets. We had been so engrossed in the amazing birding of the Perijás, we hadn’t realized that we were less than half a mile from the Venezuelan border! Despite the increase in safety over the last several years, getting too close to the border was not a risk we wanted to take (areas within 12 miles of the border are considered a “Level 4: Do Not Travel” zone by many countries), so we decided to turn back.

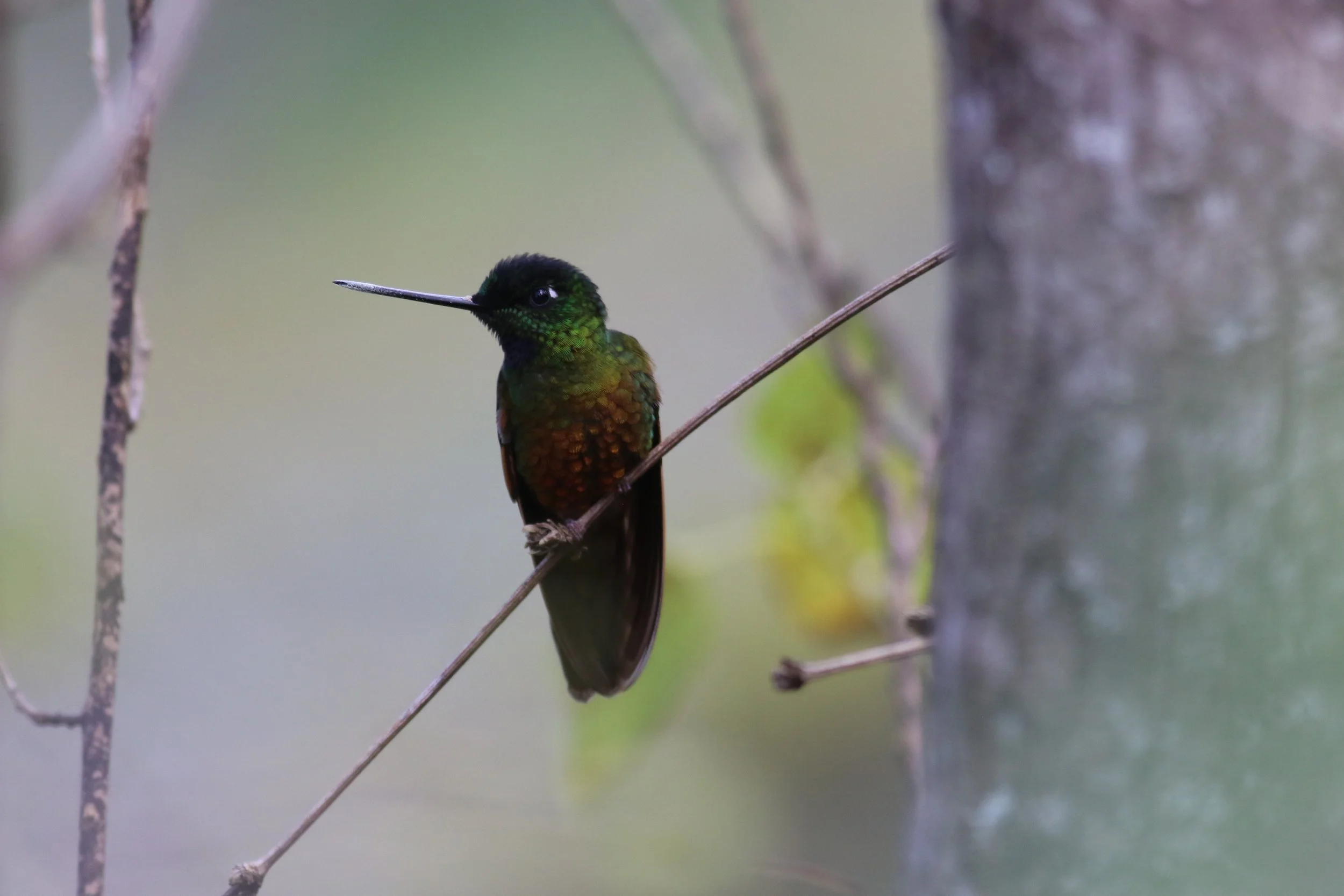

After about an hour of slowly making our way down the mountain, taking time to stop and photograph interesting plants and insects, we began to discuss our strategy to check off the final target of the day. The Perijá Starfrontlet had already eluded us in the morning, and we were determined not to let it happen again. However, after striking out at our first two pins for the species, I had started to lose a little hope. About halfway down the road, we decided to take a break and enjoy some of the amazing food prepared for us by the staff at the Perijá ProAves Reserve. It was during this break that we noticed a faint buzzing sound coming from the flowery bushes across the road from us. Expecting it to be just another Tyrian Metailtail, or Mountain Velvetbreast, I wasn’t too interested at first. Despite my low hopes, I got up and began looking around for this mystery hummingbird. To my complete shock, I looked down into an open hole in the bush, and looking back at me was an astonishingly beautiful male Perijá Starfrontlet. At the beginning of this trip, I wasnt’t hopeful that I would be able to even see this species, let alone get one of the best looks a person could ask for. The Starfrontlet didn’t hang around long, I watched this amazing bird for about 10 seconds, took a few quick photos, and it disappeared. Despite such a short encounter, I couldn’t ask for any better way to end a perfect day in the páramo of Northern Colombia

Perija Starfrontlet (Coeligena consita)

Exploring the Talamancan Mountains Part 1

I have always found alpine areas fascinating, and almost nowhere has satisfied that fascination for me more than the Talamancan mountain range of Central Costa Rica. In September I was lucky enough to spend two nights in the Talamancas iNaturalisting from the alpine forests of Paraiso Quetzal Lodge to the gorgeous Páramo habitat at over 11,000 feet of elevation.

The first wildlife I noticed when we arrived at Paraiso Quetzal were hummingbirds, and lots of them. While the entire country of Costa Rica is known for its astonishing hummingbird diversity, the Talamancas are something else entirely. Within 10 minutes of arriving at the hummingbird feeders, I had seen five lifer hummingbird species, all endemic or nearly endemic to this small stretch of mountains in Costa Rica and Panama. While all of these new species were super cool, one stood out above all others. The Fiery-throated Hummingbird looks quite unassuming at first, but when the light hits it just right, you can observe a gorgeous array of reds, oranges, yellows, greens, and blues, all over the hummingbird's body.

Fiery-throated Hummingbird

These weren’t the only new bird species I encountered at Paraiso Quetzal. Pretty soon I was seeing many of the classic Talamancan birds such as the Large-footed Finch, Sooty-capped Chlorospingus, and the elegant Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher. Walking through the native gardens and observing these birds was surreal. These were species I had been dreaming about seeing for years, and here they were, foraging on the ground just feet from where I was standing.

Long-tailed Silky Flycatcher

Despite being a fantastic birding lodge, Paraiso Quetzal had much more in store for me besides birds. After some easy birding around the grounds, and a quick dinner, I put out my moth sheet, grabbed a headlamp, and went on my first night search in the Talamancas. After exploring the dense tropical rainforests of lowland Costa Rica for the last few days, I honestly wasn’t expecting much from the cold, rainy nights of the Talamancas. I was almost immediately proven wrong. Although the wildlife was certainly different up in the mountains, there was no shortage of interesting species for me to find. The mossy trail edges were full of fascinating beetles, earwigs, crickets, plant bugs, stick insects, and more. With a 5:00 am wake up planned the next morning, I decided to head back to my room after only a couple hours of iNatting and get a good night’s rest for what was probably my most anticipated bird of the entire trip.

Praos perditus

Florida Part 1

Ever since I started seriously using iNaturalist back in 2022, South and Central Florida have been a top priority trip for me. From the pine rocklands on Big Pine Key, to the sandy Lake Wales Ridge, Florida has hundreds of endemic plants and animals that I’ve been dying to see for a very long time.

The Florida Keys are one of the most fascinating natural areas in the entire country. I began my trip on Key Largo, which is one of the only places in the world to see Sphaerodactylus notatus, or the Reef Gecko. As the only Sphaerodactylus species found in the United States, this species is at the top of my reptile bucket list. Measuring in at only 2 inches long, searching for the Reef Gecko turned out to be a very frustrating experience. After an hour of searching through the forests of Key Largo, I gave up on my search, but not without finding some pretty amazing species along the way. The Golden Silk Spider (iNaturalist Observation) was a common sight, with their webs often blocking the way to prime Reef Gecko habitats. I also saw many interesting plant species, such as the Bahama Strongbark (iNaturalist Observation) and Blackbead (iNaturalist Observation), which are mainly found in the Caribbean but have strongholds in Southern Florida.

My next stop on the drive out to Big Pine Key was the Key Tree Cactus Preserve. These fascinating cactuses have been documented to grow up to 30 feet tall but are now unfortunately facing extinction. Climate change, collecting, and stronger and more persistent hurricanes are all factors to this species' slow demise, causing 6 of the 11 known tree cactus populations to die out. Luckily for me, this species can be easily seen at the Key Tree Cactus Preserve. Five minutes after pulling into the parking lot off of Route 1, I was standing in front of one of the coolest cactus species I’ve ever seen. Pretty much every cactus species found on the East Coast is an Opuntia, or prickly pear, species, so seeing something so unique was quite refreshing.

Key Tree Cactus

While the first half of my day on the Florida Keys was amazing, it all pales in comparison to exploring the pine rocklands of Big Pine Key. With dozens of endemic species, and only four percent of the original habitat remaining, the Pine Rocklands are one of the most threatened and valuable habitats in the country. I spent several hours botanizing along Key Deer Boulevard and the Fred C. Manillo Wildlife Trail. It’s just too difficult to choose only a couple species to talk about for this part of the trip so I’ve listed some of my favorite finds below

Key Deer - Found only in Florida Keys

Big Pine Partridge Pea - Only found on Big Pine Key

Key Thatch Palm - Native to Caribbean

Grisebach’s Dwarf Morning-Glory - Native to South Florida and Cuba

Rocklands Spurge - Native to South Florida and Cuba

Pride of Big PIne - Native to Caribbean

Euphorbia ogdenii - Native to South Florida

Genus Showcase - Veronica

It's a little different from most of my posts, but I wanted to showcase the amazing diversity of the genus Veronica in New Zealand. With around 150 species, New Zealand is home to nearly a third of all Veronica species in the world.

Due to New Zealands' isolation from the rest of the world, these species have evolved to fill nearly every niche you can imagine. From coastal dunes and beaches to tropical rainforests and even the snow-covered mountain peaks of the Southern Alps.

In the 2 months I've been in New Zealand, I've multiplied my Veronica life list by 6. I've selected some of my favorites that show just how different these Veronica species can be

(For people that don't know taxonomy, this means that these species are all very closely related despite looking so different)

Veronica parviflora

Veronica hookeriana

Veronica cheesemanii

Veronica topiaria

Veronica pulvinaris

Veronica saxicola

Veronica lycopodioides

Zealandia By Night

On the outskirts of one of the most populated cities in New Zealand lies a hidden gem. Named for the continent New Zealand is a part of, Zealandia is a safe haven for hundreds of native and often endangered species. The 555-acre wildlife refuge is completely fenced off from the outside world, ensuring that no unwanted predators are able to enter. Possums, rats, stoats, and feral cats wreak havoc on native bird populations and are a major threat to dozens of native species.

My time in Zealandia began near dusk on November 13. Many of Zealandia's specialties can only be found at night when the park is closed to most guests. However, guided tours are available to those who wish to explore the nocturnal life that resides in the sanctuary. After a quick introduction to Zealandia's history and its plans for the future, we ventured out in search of some amazing wildlife.

Many bird species have a jump in activity around dusk. I watched Pied Shags coming in to roost on pondside trees while Tui and Bellbirds sang in the background. This peace only lasted for a second. Suddenly, dozens of New Zealand Kaka erupted from the trees, screeching as if to alert the valley of a danger. They had spotted a kārearea, (New Zealand Falcon) that circled the pond a few times before deciding that dealing with these boisterous parrots wasn't worth it.

As darkness fell on Zealandia, the tour group became quiet as we all scoured everywhere from the ground to the treetops for anything alive. It wasn't long until someone called out a Tuatara. I had been missing these "living dinasours" for over a month since I'd seen them on Tiritiri Matangi Island. These reptiles, viewed by the Maori as messengers of the God of death, have remained almost unchanged for over 200 million years and have become one of New Zealand;s most iconic animals. One of the few creatures that is more well known in the country is the kiwi, which was spotted by a guide not long after. Zealandia is a haven for Little Spotted Kiwi, boasting the second largest population anywhere in the world. We were able to observe two individuals on this excursion, more than making up for my lackluster experience with the species on Tiritiri Island.

Before the tour of Zealandia came to a close, there was one more surprise waiting for us hiding deep in a flax bush on the side of the track. Wētā are a group of cricket-like insects found all over New Zealand. Some, like the Wellington Tree Wētā, are dirt common in the right habitat. Others are much more special. The Cook Strait Giant Weta is one of those. This species was considered extinct on mainland New Zealand before a reintroduction to Zealandia in 2007, where their populations have soared. While not as charismatic as Kiwis or Tuatara, these wētās, with a Latin name meaning "wrinkled terrible grasshopper," was by far the highlight of my night. This wētā is a perfect of example of the amazing success of Zealandia and the power that people have to reverse our past actions and preserve the world for future generations.

Mt. Ruapehu

I’ve always been fascinated by the tens of thousands of species of plants, animals, and other life forms that have evolved to survive in harsh alpine environments. With lots of volcanic activity throughout the country, and the massive Southern Alps range stretching across the majority of the South Island, New Zealand is a paradise for these species. In the winter months, these alpine landscapes are completely barren. But with the weather starting to warm up in late October, the mountains come alive.

I recently decided to spend a couple days exploring Tongariro National Park in the central North Island. I had been trudging through thick rainforests, coastal wetlands, and muddy farm fields for the past month and needed a change of scenery. The endless rolling hills covered in rare alpine plants were calling my name and I couldn’t ignore it.

I woke up on October 29th in Whakapapa Village, and began preparations for my twelve-mile out-and-back trek to the Tama Lakes, where I expected to find plenty of new species for my list. With only a few hundred meters of elevation gain, the hike wouldn’t be the most challenging but the cold temperatures and high winds added another level of difficulty. When I first set out, It was only 29 degrees and the wind was blowing strong. I was shocked to see insects already out and about in this below-freezing temperature. Resistance to cold weather is just one of the many adaptations these species possess to survive the harsh conditions of Mount Ruapehu.

My time under the treeline was very brief and within half an hour I had moved out of the dense forest into a vast alpine shrubland. I immediately began picking out some species that I knew I hadn’t seen before. One of these was Raoulia albosericea, a plant in the family Asteraceae along with sunflowers, daisies, and other common flowers. This species has adapted to the alpine environment in a fascinating way. By being small. With each flower being only a few millimeters wide, it can essentially hide from the intense wind and cold by staying close to the ground. This was a common trend as I got higher and higher, Pimelea microphylla, Styphelia nesophila and dozens of species of moss and lichens share this strategy.

Over the next twelve miles, I observed dozens of new species and their unique adapatations. I’ve linked a list of all the iNaturalist observations I made during my time in Tongariro National Park so you can see for yourself all of the amazing species that have evolved to be able to survive the high winds, frigid temperatures, volcanic activity, and much more.

Diving Great Mercury Island

I recently had the opportunity to go on two dives off of Great Mercury Island in Northern New Zealand. This is a collection of some of my favorite species I observed on the dives.

Giant Snake Eel (Ophisurus serpens)

Eastern Kelpfish (Chironemus marmoratus)

Southern Sand Star (Luidia australiae)

Deepwater Burrfish (Allomycterus pilatus)

Southern Rock Lobster (Jasus edwardsii)

Undescribed Sea Anemone Species

Goatfish (Upeneicthys porosus)

Tiritiri Matangi - Part 2

The next three days on Tiritiri Matangi flew by. We recorded amazing numbers of many of New Zealand's endemic forest birds. I saw over two hundred Tui and Korimako, nearly three hundred Pōpokatea, twenty-five Kokako, fifty Hihi, and much more. Birding the island by day was truly amazing, but the island only really came alive at night.

My first night on Tiritiri was one of the best of my life. As I stepped out of the bunkhouse and looked to the sky, I was quite literally starstruck. Even being so close to Auckland, the starscape was one of the most amazing I've ever seen, rivaling the deserts of Arizona and the remote Galapagos Islands. The Milky Way stretched across the night sky and millions of stars were visible in every direction. As I gazed up at the night sky I realized I wouldn't be seeing any of the constellations I had known my whole life: The Big Dipper, Orion's Belt, and Pegasus for the next year and a half. These were replaced by a night sky that was completely foreign to me. I could no longer find direction with North Star, but now with the Southern Cross. I would now spend my stargazing sessions trying to pinpoint Alpha Centauri rather than Ursa Major.

My moment of realization was interrupted by the echoing call of a Little Spotted Kiwi, one of the species I'd most been looking forward to seeing on this trip. Kiwis are notorious for being tricky to spot and these were no exception. I spent several minutes trying to pinpoint it to no avail before continuing my walk. I spent the next half an hour slowly wandering through the forests of Tiritiri Island listening to the distant calls of kiwi and ruru while gazing up at the stars when suddenly I heard something rustling in the brush just a few feet from me. Thinking I had struck gold I turned my light towards the sound and came face to face with..... a duck. Pāteke (Brown Teal) is an endangered and endemic species in New Zealand and also happens to be primarily nocturnal. This particular Pāteke didn't seem too happy with me, and as I looked closer I could see why. Next to this gorgeous duck was a tiny ball of fluff, a baby Pāteke. After taking a quick photo I quickly moved on as I didn't want to stress out this already threatened species.

While kiwis were obviously one of the biggest targets of this nocturnal excursion, there was one other species I had in mind. The class Reptilia consists of four orders and approximately ten thousand species, three of which are known by almost everyone on the planet, turtles/tortoises, lizards, and snakes. The fourth order contains only one species, which can only be found in New Zealand. The Tuatara is essentially a living fossil, evolving into existence 150-250 million years ago, sometime in the Jurassic or Triassic periods. Unfortunately, in the millions of years since, Tuataras only remain in the wild on a few islands off of New Zealand, with Tiritiri being the most accessible.

I began my Tuatara search walking very slowly down a path that had been recommended to me the day before, peering into the undergrowth hoping to spot one of these dinosaurs searching for a meal. As I was nearing the bottom of the trail, where it meets the ocean, I spotted my first sign of life. It wasn't a Tuatara, but a Little Penguin that had been wandering down the trail before I scared it into the bush. It was quite apparent how these seabirds are not built for agility on land as I watched the penguin running through the woods, tripping and stumbling every couple of seconds before disappearing into the forests of Tiritiri Matangi for good.

Little Penguin at night.

I think the penguin may have been a good luck charm, as just a few minutes later I spotted my first of three Tuatara of the night. Seeing them in person made me realize how different they really are. I've observed nearly forty species of lizards in my life and this was like nothing I'd ever seen before. With their bumpy skin and spikes running down their spines, they really do look like the dinosaurs that they shared the earth with hundreds of millions of years ago.

Tuatara seen the following day.

As I began my return trek, I had another realization. This was the first day where I really felt like I was in a different world altogether. From the penguin to the dinosaur-like Tuatara to the gorgeous night sky, it was all so foreign to me. As I arrived back at the bunkhouse I took one more long look at the Southern Cross before calling it a night and getting some sleep.

Tiritiri Matangi - Part 1

At 9:00 AM on October 1st, I began one of the greatest birding experiences of my life. Three nights on Tiritiri Matangi Island, a pest-free island off the coast of Auckland, would be a dream come true for most birders, allowing them to see incredible numbers of some of New Zealand’s rarest and most charismatic endemic species.

Accompanied by seven other avid birders and nature lovers, I spent the next four days trying to see as many bird, plant, insect, and reptile species as I possibly could. This meant early mornings trying to find the impossibly small Titipounamu (Rifleman), and late nights listening for the haunting calls of kiwis, hoping that one would cross our track. While this may seem like a daunting task, for the eight of us on the island it was paradise.

Almost immediately after stepping off the ferry, I picked up the ghostly song of a North Island Kokako, an incredible New Zealand endemic that was one of my biggest targets for the trip. Kokako became a sort of mascot of our adventures on Tiritiri as we had unbelievable luck with this species over the four days on the island. We spent the next half an hour slowly making our way up to the bunkhouse watching Tūī and Korimako (New Zealand Bellbird) fight over nectar feeders while the shy Hihi (Stitchbirds) watched from a distance. The songs of dozens of amazing endemic species flooded the forests of Tiritiri Matangi, signaling the start of an amazing adventure.

After a quick lunch at the bunkhouse, we set out on our first major trek of the trip. Our first afternoon of birding started off with a bang as we spotted a lone Takahē feeding right in front of the lighthouse outside our lodging. These adorable, perfectly round birds were once thought to be extinct before being rediscovered on the South Island in 1948. In the 75 years since then, an incredible effort has gone into the repopulation of this species in their natural range. The two pairs of Takahē that reside on Tiritiri have been a major part of that effort, with their offspring being used as part of the repopulation effort.

Our luck certainly did not end with the Takahē. Over the next few hours, we saw nearly a dozen Kākāriki (Red-crowned Parakeets), a family of Pāteke (Brown Teal), and several impressive Kerurū (New Zealand Pigeons).

These New Zealand endemics, amazing in their own right, paled in comparison to what was one of the most amazing birding experiences of my life. I was deep in conversation with one of the other birders on the trip when I noticed a flash of brown out of the corner of my eye. I quickly looked down at the flax by my feet and saw a small, scruffy bird staring back at me. "Holy f***ing s**t" was my immediate reaction. It was a Mātātā (New Zealand Fernbird). While not incredibly rare, these birds are famous for being cryptic and elusive, not showing their faces to even the luckiest of birders. While losing our minds over this amazing sighting, ANOTHER Mātātā called from a nearby bush. We spent well over fifteen minutes trying to photograph one of these elusive birds to no avail, with my best picture being a blurry mess that could barely be called a bird. I was feeling a mix of emotions, from elation to frustration and everything in between. But I knew it was time to move on. Right before I opened my mouth to suggest we move on, TWO MORE Mātātā flew just inches from my leg, providing better views than I ever thought I would get of one of NZ’s most enigmatic species.

Such an amazing experience within hours of landing on Tiritiri Matangi just made me even more excited about the upcoming days of birding, botanizing, and herping that followed, and I was not disappointed.

About Me & My Journey

Now I embark on the next chapter of my life, leaving home to spend over a year on the other side of the world with the end goal of reaching 15,000 species by the time I leave Oceania.

Beginning in early 2022, my obsession with seeing as many species as I possibly could was taken to the next level. I was constantly trying to find new species around my yard and by June had swapped my telephoto birding lens for a macro I could use to more easily photograph insects and plants. While I was becoming more and more obsessed, I still needed one more big push to send me over the edge and become what I am now. In July of 2022, I attended Victor Emanuel Nature Tour’s Camp Chiricahua in Arizona. These twelve days were some of the best of my life. I, along with five other amazing young naturalists and two amazing guides saw over 1,500 species including some incredibly rare orchids, snakes, birds, butterflies, beetles, and much more. In the year and a half since then, I’ve travelled to Trinidad and Ecuador in search of those countries’ rare and endemic species, doubling my life list to nearly 5,300 where it stands today.

Now I embark on the next chapter of my life, leaving home to spend over a year on the other side of the world with the end goal of reaching 15,000 species by the time I leave Oceania. I’ll be throwing away my comfortable way of living to spend every night in a car, eat beans and rice for almost every meal, and spend every waking hour searching for some of the world’s rarest species. It’s a sacrifice I’m willing to make, and it’s necessary if I’m going to hit my end goal of 100,000 species by the end of my life.